Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is a biological mechanism that controls gene expression. RNAi controls gene expression, development, and viral defense. While RNAi has been extensively studied and used for gene silencing in various research areas, including antiviral and anticancer therapies, its application as an antifungal therapy against IPA in humans is still in the early stages of exploration.1, 2, 3 The idea behind using RNAi as an antifungal therapy is to target specific genes or gene products essential for the survival or virulence of Aspergillus species.4 Silencing these genes has the potential to reduce the proliferation and pathogenicity of the fungi, which could improve the efficacy of treatment.2, 5 While RNAi has shown some promise in treating Aspergillus, most of the research done on the topic has been conducted in controlled laboratory or animal environments. The core principle of employing RNAi against Aspergillosis is to selective target and silence specific genes or gene products important for the survival or pathogenicity of Aspergillus species.6 By blocking the expression of these essential genes, it is feasible to impede the growth and pathogenicity of the fungi, potentially boosting the effectiveness of treatment. Several studies have shown favorable evidence for the feasibility of RNAi-based antifungal therapy against IPA.7

IPA is a fungal infection caused by Aspergillus species, and it poses significant challenges to human health, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems. This group of fungi is ubiquitous in the environment and commonly found in soil, decaying organic matter, and indoor environments.8, 9 While there are many species of Aspergillus, the one most frequently associated with human disease is A. fumigatus.5 Other species, such as A. flavus, A. niger, and A. terreus can also cause infections.2, 10 Its spores are microscopic and easily dispersed in the air. When inhaled, they can reach the respiratory system and potentially cause infection, particularly in individuals with compromised immune systems or underlying respiratory conditions.11 However, not everyone exposed to Aspergillus spores develops an infection, as the immune system is generally able to neutralize them. There are different types of aspergillosis, ranging from mild allergic reactions to invasive and life-threatening infections.12 Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is an allergic response in individuals with asthma or cystic fibrosis, resulting in respiratory symptoms. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) primarily affects individuals with underlying lung conditions, causing long-term lung damage. Invasive aspergillosis is the most severe form, occurring mainly in immunocompromised individuals and potentially spreading beyond the lungs to other organs, leading to significant morbidity and mortality.13, 14 Many researchers are focusing their attention on critical genes that are currently engaged in the formation of fungal cell walls or signaling pathways. Researchers have been able to successfully inhibit the growth of Aspergillus in the laboratory as well as in animal models by delivering tiny interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that selectively target these genes. This has allowed them to diminish the virulence of the fungus.15 In the review study of IPA, RNA interference (RNAi) has been used as an antifungal drug by targeting genes needed for fungal cell wall formation and signal transmission. In experimental settings, tiny interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that preferentially target these genes have been shown to inhibit Aspergillus growth and decrease pathogenicity.

Chemistry of RNAi

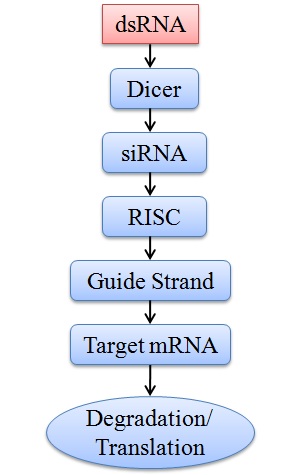

RNAi begins with the synthesis of short double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules. They are synthesized by using enzymes known as RNA polymerase II and III that are responsible for microRNA synthesis. In the presence of the microprocessor multi-protein complex and co-factor DiGeorge syndrome Critical Region 8 (DGCR8/Pasha), primary microRNAs (pri-miRNA) is turned into precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA).16 They are complementary to the target gene's messenger RNA (mRNA). These dsRNA molecules can be created synthetically or produced naturally within cells. The dsRNA is then processed by an enzyme called Dicer, which cleaves it into smaller fragments known as small interfering RNA (siRNA). The siRNA is then loaded onto a protein complex called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). One strand of the siRNA is kept safe within the RISC, while the other is thrown away. The last strand of siRNA directs the RISC complex to the target mRNA, where it attaches, which either causes the mRNA to be degraded or stops it from being translated into protein (Figure 1). This mechanism allows for accurate gene control and efficiently lowers the expression of the target gene.17, 18

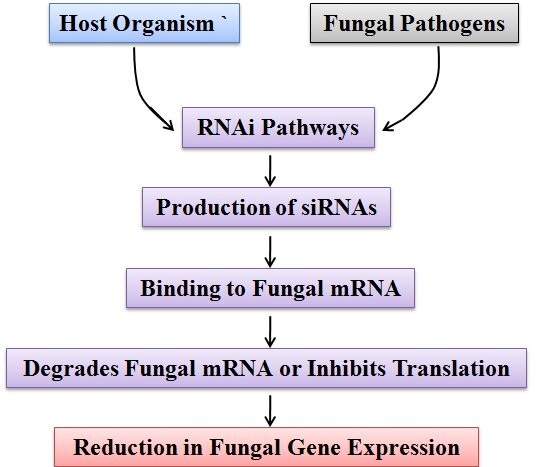

The RNA interference (RNAi) complex plays a critical role in combating fungal infections by targeting and inhibiting the expression of specific fungal genes. When the host organism detects the presence of fungal pathogens, it activates the RNAi pathway as a defense mechanism.4 The pathway leads to the production of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that can selectively bind to complementary sequences in fungal mRNA. This binding leads to the degradation of the fungal mRNA or inhibits its translation, effectively reducing the expression of essential fungal genes. By disrupting fungal gene expression, RNAi helps to control and mitigate the spread of fungal infections in the host organism.19, 20 The RNAi complex can act both in the host organism's cells and as an extracellular defense mechanism. Inside the host cells, it prevents the replication and spread of fungal pathogens by silencing their genes. Outside the cells, the RNAi complex can be secreted and released into the extracellular space, where it can directly target and neutralize fungal elements.21 In addition to its direct antifungal effects, the RNAi complex can also stimulate the host immune response. It can activate immune cells and enhance their ability to recognize and eliminate fungal invaders.22 This collaboration between the RNAi complex and the immune system further strengthens the host's defense against fungal infections. Overall, the RNAi complex plays a crucial role in combating fungal infections by selectively targeting and suppressing fungal gene expression.23 Its ability to disrupt vital fungal genes and stimulate the immune response makes it a promising avenue for the development of novel antifungal therapies.

Function of MicroRNAs in Immune Control

The involvement of microRNAs in the regulation of immunological responses, including the formation, development, activation, functioning, and ageing of different types of immune cells, has been the subject of a vast number of publications. It has been discovered that many different miRNAs display extremely specialized expression patterns in organs that are connected with the immune system's function. Even the transformation of progenitor cells of the hematopoietic system down the path of the lymphoid or myeloid lineage can be controlled by the expression profile of distinct microRNA.24 This strongly points to the fact that miRNAs play a substantial role in the development and operation of immune cells. The impact that microRNAs have on the progression of a wide range of diseases is due to the fact that they have an effect on both the innate and adaptive immune responses. Therefore, it is essential to have an understanding of how diverse physiological functions of the body's immune system are regulated by miRNAs, both in a healthy condition and in a sick state.25, 26, 27

The miRNAs involved in Inflammation during Aspergillus Infection

IPA kills more than 80% of immunocompromised people, including patients with blood cancers and bone marrow transplant recipients. Although the true prevalence of IPA remains unclear, it was once thought that between 30% and 50% of invasive fungal illnesses in immunocompromised people were caused by this condition. Because of the growing body of evidence that miRNAs control host responses to viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, it is likely that they play a role in IPA pathogenesis, which is still little understood.23 Although miRNAs have been studied in many illnesses, their function in understanding the immune response to pulmonary and systemic fungal exposure is still developing. Fungal pathogens may affect miRNA genetic network signaling and shift expression profiles during disease progression.28, 29 MicroRNAs regulate most biological activities endogenously. Freely circulating miRNAs may be biomarkers for extrapolative illnesses, according to recent studies. Hypoxia-related miRNAs, such as miRNA-26a, miRNA -26b, miRNA -21, and miRNA -101, were considered when lung hypoxia became apparent due to an ischemic microenvironment, vascular invasion, thrombosis, and antiangiogenic factors like gliotoxin.30, 31 A study examined miRNA -132 and miRNA -155 expression among human monocytes and dendritic cells following A. fumigatus infection. A. fumigatus, or bacterial lipopolysaccharide induction, differently expressed miRNA -132 and miRNA -155 in monocytes and DCs. Surprisingly; A. fumigatus activated miRNA -132 in monocytes and DCs, whereas LPS did not. This suggests that miRNA -132 may regulate the immune response against A. fumigatus.32

The most common causes of aspergillosis are the fungi A. fumigatus and A. flavus. Clinical observations and serological tests form the backbone of the diagnostic process. After a lung biopsy or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), histological testing and tissue culture are the gold standards. However, in severe cases like thrombocytopenia, this intrusive method is not recommended. Due to the lack of an immediately available standard diagnostic test, the high mortality rate associated with IPA poses a significant problem.33, 34, 35

Chen and his team initially worked on the inflammation due to IPA. They injected cyclophosphamide intraperitoneally into mice to create a neutropenic model and found that the mice's neutrophil count remained below 100/mm3 throughout the study. A. fumigatus was able to infect mice with weakened immune systems. On day four after the infection, the mice stopped eating, stopped moving around, and eventually stopped breathing. On day one post-inoculation, infected lung tissues had the highest fungal burden, which decreased with time. Gross pathologic alterations included a rise in bleeding as well as the development of white nodular lesions. A group of hyphae was seen under the microscope when A. fumigatus spores germinated in lung tissue.36 These findings demonstrated the validity of the IPA mouse model. For this they used NGS to perform a global miRNA profile in the lung tissues of mice that had either been exposed to IPA or served as controls. Our goal was to determine which and how many miRNAs are likely implicated in the pathogenesis of IPA.37

The genus Aspergillus contains numerous species of filamentous fungi that are widely distributed around the globe and can be found in a wide variety of habitats. The most common member of this genus, A. fumigatus, is largely responsible for the rise in the incidence of invasive aspergillosis, which carries a significant fatality rate in immunocompromised patients.38, 39 A. fumigatus is currently the leading cause of death in leukaemia patients and is responsible for a high number of nosocomial opportunistic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts, especially during cytotoxic chemotherapy and following bone marrow transplantation.40 Conidia (resting spores) of Aspergillus are found everywhere, are frequently breathed, and are rapidly phagocytized by the alveolar macrophages and neutrophils of an immunocompetent host. However, if immunocompromised people are unable to effectively germinate conidia, they may get invasive pneumonia and systemic infections.31 It has been used as a model to investigate the function of the cell wall in the evolution and pathogenesis of filamentous fungi because of its clinical importance.

Following an infection, there are discernible shifts in the profiles of the circulating microRNAs. It has been demonstrated that an infection with Candida albicans causes an increase in the production of several microRNAs, including miR-455, miR-125a, miR-146, and miR-155, in the macrophages of rats.41 In rats with candidemia-induced kidney damage, the expression of miR-204 and miR-211 was found to be reduced in kidney tissue.42 Both miR-132 and miR-155 revealed increased levels of expression in monocytes and dendritic cells that had been infected with A. fumigatus.31, 41 The patients who were infected with P. brasiliensis had elevated expression of 8 microRNAs that were connected to apoptosis and immunological response, according to the serum study. The information in Table 1 illustrates how IPA may cause certain essential miRNA to become potentially active.

Table 1

List of miRNA involved in Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

Perspectives of miRNAs during IPA

MiRNAs have been found to play a role in the development and progression of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), an opportunistic infection caused by the fungal pathogens like A. fumigatus, A. flavus and many more. MiRNAs regulate gene expression in response to environmental signals, and studies have shown that miRNA expression profiles differ in IPA patients compared to healthy individuals. These differentially expressed miRNAs have been found to modulate the immune response to fungal infection in various ways, including by promoting apoptosis, decreasing antibody production, and decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.50 Additionally, miRNAs have been identified that promote the proliferation and differentiation of pulmonary cells, suggesting a potential for miRNA therapy in IPA. As research on miRNAs and IPA continues to develop, patient management protocols may be altered to provide therapies targeting the disease-associated miRNAs. Recent studies have focused on this phenomenon in fungi and its involvement in fungal infections. In particular, miRNAs can modulate the expression level of target genes involved in the initiation, perpetuation, and/or maintenance of fungal infections. This includes regulation of pathogenicity, adherence, infectivity, and evasion from the host immune system.

Conclusion

The significance of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the arms race between hosts and pathogens is a topic that needs greater attention in the future. It is not well known, for instance, how fungal infections secrete and transmit short RNA effectors to the plant host or how the plant exports sRNAs to induce cross-kingdom gene silencing. The regulatory role of miRNA networks in plant innate immunity will be better understood as a result of future studies into the biological function of miRNAs, which were previously thought to be a byproduct of miRNA synthesis. Opportunities for the development of novel tactics and technology to enhance human resistance to pathogens are also presented by miRNAs and their targets.