Introduction

Antimicrobial agents are among the most frequently prescribed drugs and Antimicrobial resistance is more prevalent in hospital settings due to unrestricted and improper use of antimicrobials1,2 Approximately one third of patients admitted to hospital receive antibiotics during their hospital stay3,4 and reports say that up to 50% of all courses of antimicrobial therapy are deemed unnecessary.3,4,5 Antimicrobial resistance is of great concern also because it is associated with increased patient ’s duration of hospitalisation, expenditure, and fatality rate.6

Since both frequent and prolonged use of antimicrobial agents may promote the emergence of resistance,7,8 antimicrobial stewardship is recommended as a means of reducing antimicrobial resistance, along with lowering the risk of adverse drug events, treatment complicati ons, and institutional costs. 9,10 It is important for institutions to understand their patterns of antimicrobial use to identify appropriate stewardship interventions that have the greatest likelihood of impacting institutional antimicrobial utilization and therefore, aforementioned consequences of antibiotics use. Analysing the antimicrobial use pattern can provide statistics from which explicit antimicrobial stewardship interventions can be targeted.

Several studies have assessed the relationship between differences in prescribing patterns and the occurrence of resistance in bacterial isolates. These data have provided background for the introduction of antibiotics restriction and cycling of antibiotics to fight for the emergence of antibiotic resistance8,10,11. Based on an ecological study in Europe, countries with higher antibiotic consumption had correspondingly higher rates of anti biotics resistance, highlighting the fact that uncontrolled prescription of antibiotics is a key risk factor for resistance.8 Further support for this link was evident by the decrease of resistance with reduced prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which was also associat ed with a cost-saving outcome.10

Many factors can lead to fluctuations and misuse in antibiotic use, such as over-prescription of broad-spectrum antibiotics and inappropriate treatment of likely viral respiratory tract infections. 12 Indeed, the lack of prescriber’s perception of the effect of antibiotics on the emergence of resistance remains a key driver of inappropriate antimicrobial use and rates of resistance.10

The world’s largest consumer of antibiotics for human health was India, as reported in 2010 and which happens to be 12.9 x 109 units (10.7 units per person).13 The Government of India has issued a National Policy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance which promotes antimicrobial use surveillance in the community and hospitals. To begin with, the Government proposed the drug utilization studies of antimicrobials in hospitals. Also, it suggests that the data on consumption trends can be used for intervention studies to promote the rational use of these medicines. Hence fundamental components of the stewardship program are to measure the quantity & Quality of antibiotic use.

Defined daily doses (DDD) of prescribed antimicrobials per 100 bed days are a good quantitative measure of antimicrobial consumption. And point prevalence survey in a structured way helps in the qualitative assessment of Antimicrobial use at a given point of time. The main disadvantage of the quantitative approach is if it can actually measure the quality of antibiotic prescribing. Hence PPS can help to target the areas for quality improvement in antibiotic prescribing, establish interventions to promote better stewardship of antibiotics to assist in fight against antimicrobial resistance and a praise the validity of interventions through periodic surveys. A PPS serves as a convenient, inexpensive surveillance system of antimicrobial consumption, as opposed to continuous surveillance.

PPS is an established stewardship tool in few countries, but in some parts of the world, clinicians have just begun to understand and explore how to use it. There are very few Indian studies on Point prevalent survey of antibiotic use, and to the best of our knowledge, our study is probably the first from South India.

In this study, a point prevalence survey was conducted to measure antimicrobial utilization and patterns of use at a tertiary care teaching hospital for inpatients. For future point-prevalence surveys we hope to use this information as baseline data. Also, the effect of antimicrobial stewardship interventions will be determined, and it will bring out awareness among prescribers regarding appropriate AU.

Aims and Objectives

To determine the prevalence of patients receiving at least one antimicrobial agent and the prevalence of individual antibiotics prescription from specific Wards & ICU on the survey date.

To outline the antimicrobial prescribing pattern (choice of antimicrobial agent, indication, route and, duration of therapy).

To study relationships existing between Empiric/Definitive AU for CAI/ HAI and Surgical antibiotics prophylaxis with relevance to the anatomic site.

Materials and Methods

The point prevalence survey was conducted at 670 bedded teaching hospitals in South India. This hospital provides tertiary medical care in twenty-eight wards, including three ICUs spanning paediatric, medical and surgical units.

Study period

One week period to assess rational antibiotic s prescriptions by Point prevalence study during the last week of January 2019

Study tool

In the house, simple PPS tool was prepared based on point prevalence survey methodology on antibiotic use in hospitals from WHO- version 1.1 as a reference tool.14,15

Data collection

A multidisciplinary survey team conducted the PPS and collected the relevant data at selected units. The survey team was trained on how to aggregate the information before the start of the survey. Briefly, the training session lead by the principal investiga tor who introduced survey personnel to the aims & objectives of the study; the purpose for collection of each item on the data collection tool including terms and indicator codes definitions; methodology for evaluating individual patient data; and each survey personnel roles and responsibilities. For a period of one week, the point prevalence survey was conducted by the survey team within 8 hours from 8 am to 4 pm daily. The survey team performed data collection using a PPS tool (based on WHO methodology) which comprised of a patient-level structured template to document antibiotics use on the survey date. The team also reviewed admitted patients’ treatment charts and recorded antibiotics used on the survey date. Patients’ demographics like age, sex, admitted ward, and total numbers of patients on admission on survey day were noted. Other appropriate information such as administered antibiotics, its route of administration, dosages, dosing intervals were also included. Addition al information recorded w as information on patients’ clinical diagnosis and antibiotic use indications.

Indication for AU

As defined by WHO14,15 Indication for AU was noted for hospital-or community-acquired infections (HAI, CAI) or for Surgical/Medical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP /MAP) or Unknown. The team re viewed signs & Symptoms from medical and nursing case records and other relevant charts to identify if the indication is a HAI/CAI/SAP/MAP.

The survey team’s decision if a patient was infected (HAI/CAI) was based on clinical grounds and WHO PPS guideline definitions. Actively infected patients were diagnosed by the presence of signs and symptoms on the survey date. Also, they were considered infected when the patient was still receiving treatment for that infection on the date of the survey even when signs and symptoms were no longer present. Clinical diagnosis of hospital-acquired infections describes infections occurring 48h after admission and categorized as community-acquired if occurring within 48h of admission.

Antimicrobial use for CAI/HAI was identified as being definitive or empiric. Definitive treatment was defined “when the patient underwent antibiotic treatment following the identification of either a site of infection or isolation and reporting of infecting pathogenic microorganism”. Empiric treatment was defined as “one that was started for a presumed or possible infection without a site or infecting organism being identified”.

Prophylaxis was defined as “the use of an antimicrobial agent to prevent infection when an infection was not already present”. Treatment indication was categorized as unknown “if there was no identifiable reason for antimicrobial use after review of the medical records”. The classification of drugs was based on WHO anatomical therapeutic classification (ATC) of medicines

Targeted antimicrobials

Includes Beta lactams, fluoroquinolones, third -generation cephalosporins (3GC), carbapenems, aminoglycosides, vancomycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who were receiving at least one systemic antibacterial, on the day of the survey.

Exclusion criteria

Patients undergoing same-day treatment or surgery

Emergency room patients who were not yet admitted

Palliative care patients

Ophthalmology ward s and dermatology ward patients were also excluded from the survey because mostly these patients will be treated with Topical antibiotics.

Orders for anti-retroviral, anti-tuberculosis, antifungal and anti-parasitic medications were also excluded from the survey.

Results

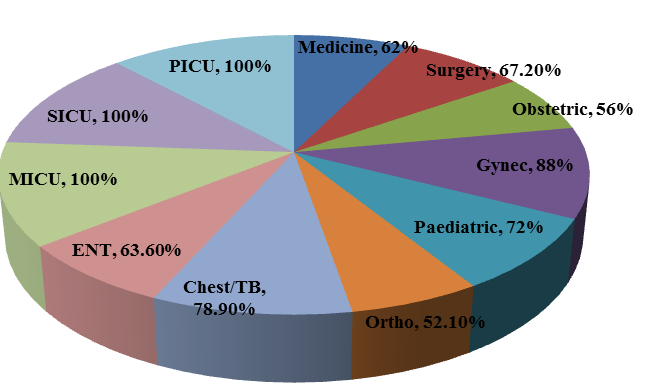

Total of 502 admitted patients w ere included in the study. Among the 502 patients, prevalence rate of antibiotic use in different wards & ICU ’s was 64.7 %(325 patients). All the ICU patients (100%) were on at least one antibiotic and the highest rate of antibiotic use was in Gynaecology ward (88.0 %) when compared to other wards Figure 1. More than one antibiotic was administered for 45% of patients and switch of IV to Oral antibiotics was reported in 27.69% of patients. The mean age of the patients on antibiotic orders (SD) was 39.

Indications for Antibiotic use in the surveyed locations were shown in Figure 2 and 51.4 % indication was for CAI followed by surgical prophylaxis (30.2%). This also compares the empiric and definitive indication for CAI and HAI in different wards &ICU’s. Both CAI and HAI were mostly treated empirically rather than by targeted therapy. The overall major class of antibiotics used were third generation Cephalosporin’s ( 3GC)-44%, foll owed by Penicillins (14.4%) and Metronidazole (12%) as shown in Table 1. and the most common antibiotic prescribed was Cefotaxim (36.9%). Across all specialties, the most common preferred choice of antibiotic used was 3GC with nearly half of the admitted patients receiving 3-GC. A significant proportion of prescribed antibiotics (69%) were administered via the parenteral route. The highest rate of parenteral antibiotics was used in Paediatrics’ and ICU’s. Distribution of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis by anatomic site infections is shown in Table 2 and 3GC was the prevalent antibiotics used as surgical prophylaxis for all anatomic sites

Figure 1

Prevalence of Antibiotics use across various disciplines in the tertiary care hospital in the year 2019, South India

Table 1

Prevalence of Antibiotics use across various disciplines in the tertiary care hospital in year Jan 2019, South India

Table 2

Distribution of antibiotics used for SURGICAL PROPHYLAXIS by ANATOMC SITE infections

Discussion

Point prevalence surveys on AU may be considered a simple method of monitoring the effectiveness of antibiotic policies and of providing useful data on patterns of antibiotic use, thus informing and guiding local and national antibiotic stewardship.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate Antibiotics prescribing patterns and to identify areas for further work where improved use of antibiotics needs to be addressed. Good outcomes with antimicrobials (i.e. appropriate antimicrobial prescribing and reduction of resistance to antimicrobials) require the use of antimicrobial stewardship approaches and completion of PPS at regular intervals16.

PPS survey in this study revealed that the prevalence of patients who received at least one antimicrobial agent was 64.74%. Community-acquired infection was the most common indication for antibiotic use followed by surgical prophylaxis Figure 2 . A significant percentage of antibiotics (69 %) were administered via Intra venous route. The highest use of parenteral antibiotics was found in ICU’s and Paediatrics wards.

We report a higher rate of AU when compared with two national studies - 51.6% & 61.5%,17,18 Ghana (51%)19 Canada (29%) 20, Egypt ( 59%)21 , Turkey (54.6%) 22, Italy (47%) 23, Australia (46%) 24, the United Kingdom (40.9%) 25, Latvia (39%) 26 & United States (33% ) .27 However, it was lower than in Kenya (67.7%),28 Iran (66.6%)29 and China (78.2%).30 In Consistent with other studies, we also observed that the majority of the antimicrobial usage was for therapeutic purposes rather than prophylaxis .26,27,29,31

Major proportions of antibiotics were mainly used for the treatment of community-acquired infections (51.4%) and surgical prophylaxis (30.2%) as shown in Figure 2 . Prevalence rate reported in this study is comparable to an Indian study 32 which reports 55.6% of antibiotics used for CAI & 18.9% for Prophylaxis. Our data is high when compared to another Indian study where is 36.8% for CAI and 35% for prophylaxis and 40% CAI and 33% SAP as reported in Ghana 19 . In contrast, reports from Egypt 21 and Kenya30 show that most common indication was for SAP ( 38.4%) and MAP (29%) respectively.

On reviewing empirical antimicrobial therapies with CAI, the two most common antimicrobials were 3GC(38%) followed by Ampicillin (15%). The antimicrobial regimens prescribed for surgical prophylaxis include 3GC (48.2%), Metronidazole (42%) and Aminoglycosides (13%). This is probably the first study describing antimicrobial use in South India using point prevalence survey.

The most commonly prescribed antibiotics in this study were 3GCs. Two other Indian studies that reviewed antibiotic prescription practices among hospitalized children in two private hospitals in central India reported similar findings.33,18

In Concordance with our findings, 3GCs were the most commonly prescribed antimicrobials in many studies from different geographical locations like Eastern Europe (35.7%) and Asia (28.6%) in the global ARPEC (Antibiotic resistance & prescribing in European children) study 31, Turkey (18.4%) 22, Italy (20%)23, Latvia (28%),26 & Iran (43.5%).30 However, studies from The United Kingdom & Australia report penicillin plus enzyme inhibitor combinations as the most commonly prescribed antimicrobials.24,25 Carbapenem prescription in this study was lower than in Turkey (12.7%) 22, Italy (6%)23 Iran (5.2%)29, Australia (3.2%) 24, but higher than in Latvia (0.5%)26.

The current guidelines recommend the use of third-generation Cephalosporins only when first-line agents are ineffective 34. Hence this study identified an opportunity to improve antimicrobial use by prescribing first line drugs for hospitalized CAI patients.

A recent study analysing the antibiotic sensitivity of the major bacterial pathogens isolated from community-acquired pneumonia in India indicated high susceptibility to first-line agents (Ampicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) 35. This study reinforces that third-generation cephalosporins can be avoided as first-line therapy for respiratory CAIs.

According to CDDEP(Center for disease dynamics, economics & Policy) antimicrobial resistance surveillance data 36 obtained both from all age groups, in 2017, 77% of the Eshericia coli isolates were resistant to 3GC in India, which was much higher than in Australia (11%), the United Kingdom (11%), Argentina (17%), the United States (13%), South Africa (19%), and China (63%) 36. Exposure of 3GC in children could lead to earlier colonization, which facilitates the spread of Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase producing bacteria among family members. This leads to a further increase in prevalence of ESBL Enterobacteriaceae infections in India and subsequently the consumption of Carbapenems. Our findings in a study published in 2018 indicate the need for increased compliance with national guidelines 37.

Therefore, antimicrobial stewardship initiatives targeting these indications may have the greatest potential to impact on patient care, antimicrobial use, the incidence of nosocomial infections, and resistance. Another area for antimicrobial stewardship intervention, as suggested in previous surveys is with antimicrobial surgical prophylaxis.

The second most common indication for antibiotic administration reported was surgical prophylaxis accounting for 31.4% of all antibiotic prescriptions. Also, our observation that 3GCs were the most commonly used antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis is not in par with the published international guidelines which recommends the use of first-and second-generation cephalosporins instead of third-generation cephalosporins 38. A detailed review of surgical prophylaxis prescriptions revealed that the selection, timing, and duration of administration were frequently inconsistent with the evidence-based practices. Approximately three fourth of patients receiving surgical prophylaxis, were treated with SAP for greater than 24 h at the time of this survey. First-generation Cephalosporins and Penicillins were used for SAP which accounted for 7.4 % of all antibiotic agents even though these are the recommended agents for a large proportion of surgical procedures 38. And 52.2% of surgical prophylaxis prescriptions were from Broad-spectrum agents such as 3GC and beta-lactam plus beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations, which might contribute to increase in multidrug-resistant organisms’ emergence. In response to these findings, our hospital has proposed a quality improvement project focused on improving surgical site infection prevention practices, including surgical antibiotic prophylaxis.

This study has important limitations inherent to the use of point prevalence surveys like a single point in time and so the results can be affected by normal day-to-day variation, existing trends, and seasonality of antimicrobial use. Since they are more likely to overlap the study date, differences in patient population and prescribing practices should be considered when comparing these results to other institutional point prevalence surveys. But given the availability of national treatment guidelines and similarities in prescribing practices among academic teaching hospitals, the results of this survey provides a good initial estimation of institutional antimicrobial use in South India.

Few Clinicians are aware of National antibiotic use guidelines and even if they are aware, adherence to antibiotic guidelines (compliance rate) is low. To improve rational antibiotics use, such guidelines need to be incorporated in Hospital antibiotic policies and translated in to practice. This may result in a reduction in hospital antibiotic consumption & its associated complications.

Conclusion

This prospective point prevalence survey provided important baseline information on antimicrobial use and identified potential targets for future antimicrobial stewardship initiatives at our tertiary care teaching hospital. This study reports a high prevalence of antibiotic use among inpatients with a relatively high prevalence among General medicine & paediatrics patients. There is a high use of 3GC&Metronidazole and low percentage use of higher antibiotics like Meropenem. Majority of the antibiotics use indications were community -acquired infections and surgical prophylaxis.